|

3.1. How a Stream Works

The basic structure of a stream influences its health and ability to provide habitat. Stream structure is a balance of its soils, water table levels, and land elevations, creating a habitat that is unique with each stream. Understanding this balance is important: enhancement of habitat often corrects problems that occur when people tamper with its balance.

The structure of a stream is defined by:

- Water flow features (the stream's pools, riffles or other

specialized sections)

- Channel (the stream's width and shape)

Let's look at each one of these so we understand what they mean.

|

|

|

Water flow Features

The flow of a stream can be broken down into four main areas

- Riffles

- Pools

- Runs

- Flats

|

|

3.1.1

Waterflow Features

Riffles

These are the swift, shallow portions of streams or

rivers where the water surface is broken. Often rocks

protrude through the water surface. The stream bottom

is usually gravel and rock. Riffles are important areas

for two major reasons. Most of the food supply for salmon

or trout is produced on them and young salmon will establish

feeding territories here during the summer. Salmon that

are laying eggs (spawning) select areas where water

is seeping through the gravel. These areas are usually

found at the tail of a pool or at the head of a riffle.

Runs

These are swift, deep portions of streams or rivers.

Although water flow in a run may be as swift as in a

riffle, the water is deeper. Runs can range in depths

(depending on stream size) from 20 cm to 2 meters (8

in. to 6.6 ft.) deep. The stream bottom is usually rock

and boulder.

Pools

These are slow, deep portions of rivers and streams

(in proportion to the watercourse's size). Pools can

be of various depths, but are the deepest areas of a

stream. The bottom can be gravel, rock, boulder, silt

or log-strewn. Pools provide living areas for a variety

of fish. These slow, deep areas are a refuge in the

winter for many species of fish, and provide ideal cover

for some of the largest trout. Pools are critical habitat

for salmon during low flow periods in the summer and

winter, for the migration of adults as holding and resting

areas, for spawning adults holding areas and as winter

habitat for pre-smolts. During normal flows pools are

dominated by trout, and the size of the pool and available

instream cover, are the major determining factors on

how many, and how large a trout, can live there. The

largest numbers of speckled and brown trout are found

in pools.

Flats

These are the shallow, slow portions of streams, usually

located at a point where the watercourse widens. A flat

can be as shallow as a riffle, but is much slower-moving.

The pattern in which these four features occur depends

on the soil-type, vegetation, slope, and amount of water

flow. In most normal streams there is a sequence of

shallow to deep water over a section of river. Scientists

call this the riffle:pool ratio. In your watercourse

project you may need to balance the riffle:pool ratio.

Habitat biologists can help you determine whether this

is necessary and if so, how to do it.

|

| A healthy

river will have a mixture of the four physical features.

The manner in which they are mixed is unique for each

stream, creating its individual character and appeal.

|

A healthy stream

channel adjusts to change naturally without changing

its basic shape and form

|

3.1.2 Typical Stream

Channel Patterns

Gravity, friction, and depth

of flow are the three main forces that create stream channels.

- Gravity causes water to move downstream and gives it

speed, while friction between water and the streambed

and banks creates a turbulence that slows down the flow.

|

|

- Friction increases in a stream when water flows over large

materials such as rocks, boulders and debris. The size and amount

of material determines the stream's "roughness"

- The speed of the water flow depends not only on slope and

roughness of the streambed, but also "on the depth of flow".

As the water level rises, the friction on the bottom and sides

has less and less influence on the speed of the flow. Basically

what happens is that water is now flowing over water and a stream

is said to be "streaming". At this point, the internal strength

of the water keeps it from pulling apart and causes it to slosh

from side to side slowing the stream down. You can observe this

effect by watching water run down a chute or a trough. |

|

|

Natural streams are seldom straight.

Streams curve around in a winding pattern or meander.

These meanders are formed by the way the water flows.

|

|

A combination of the forces described above create the

physical features of a stream (riffles, pools, flats,

and runs), and the shape of the channel.

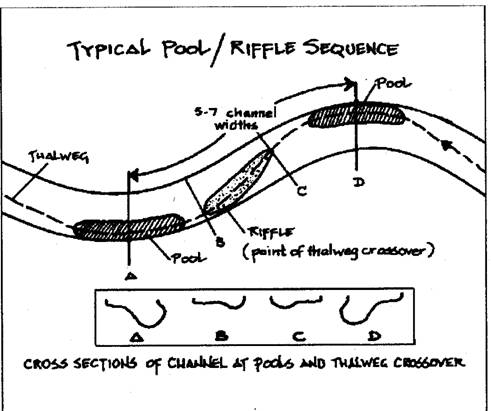

The illustration below shows a typical pool/riffle sequence

|

|

If the stream is flowing

over a mix of sand, gravel, or cobble (glacial till),

it will form a nicely shaped channel.

The pools occur at intervals in the river, spaced

5 to 7 times the width of the river channel.

Over other kinds of stream bottoms, such as sand or

boulders, the pattern is not as clear.

|

When the

water is streaming, on the outside of a bend, the water

is actually higher on the outside than inside of the turn.

The water falls with gravity, under the main flow, to

dig a pool. The heaviest material is dropped first, then

gravel to build the head of a riffle, then silt and sand

are deposited on the inside of the bend. Essentially at

this point, the flow of the water is sorting the bottom

material by size.

In shallow areas along the banks that go dry in low flow,

vegetation, such as reeds, grasses, and willows, begin

to grow. These plants also influence stream structure

by slowing down the flow of high water running through

them and by collecting debris, silt, and sand which build

up the banks at these points, narrowing the stream. The

roots stabilize the banks so as the water goes around

a bend it digs down and under, creating deeper pools and

undercut banks.

Logs falling in the stream often catch at the end of a

riffle or the beginning of a pool because the flow of

the water is slower here. These logs alter the stream

bottom to giving the gravels of the riffle and run a firm

base to pile up keeping it out of the pool. The small

head difference across the log aids in deepening the pools.

Logs and other large debris (called large organic debris

or LOD) are essential in streams to create good pools,

habitat diversity, and cover for fish.

Logs in the streams rot very slowly because they are always

wet. Hardwoods withstand the impact of sand and gravels

and are most commonly found as natural digger logs. Softwoods

usually "pulp" quickly and are gone in a couple of years.

Therefore, hardwood debris is very important in streams.

Three general terms are used to define the basic types

of stream channels:.

Straight: Applies

to sections or reaches of rivers that are relatively straight

over a long distance. Such reaches are generally unstable.

Even though the channel is straight, the water still bounces

back and forth as it travels down the channel.

Braided: Applies to

sections that have poorly defined, unstable and steep

banks, and shallow watercourse with many channels around

small islands. Too much sediment coming from tributaries

or the crumbling, eroded banks often create the islands.

Meandering:

Applies to sections with a single channel that has many

bends, or "meanders", giving an "S" shaped pattern.

A stream will always attempt to maintain its meander shape

and pattern. This curving pattern is formed by the water

flood flows and is the pattern which is in balance with

the substrate and banks to form a stable stream. Even

when a stream channel appears straight, the line of its

deepest point (thalweg) meanders back and forth across

the channel in a predictable pattern.

You may wonder what the meandering of a stream has to

do with adopting it. It is important to stress at this

point that you will be working with a natural system that

has its own natural patterns. In the Adopt-A-Stream program

we are trying to work with a natural system and help it

repair itself. If you don't understand the "natural flow"

of the stream you are working on, you might end up working

against nature, instead of with it. |

|

When

obstructions in a stream cause it to depart from the

normal meander shape, the stream will always tend to

try to get back to its natural meandering. |

Here

are some general principles that will help you understand

a stream's meandering:

- The width of the stream and the length of the curves

or meanders are closely related. If you imagine that a

meander is a piece of string that you can straighten out,

the length of the curve would be about 5-7 times larger

than the width of the stream.

- When unstable stream banks become reinforced with rocks

or plants the stream will tend to deepen and become more

stable. At any given time streams are carrying all kinds

of different materials such as particles of earth, plants,

and debris. The way these materials are moved around and

dropped off at various points affects a stream's shape

and structure.

- When you look at a stream you probably think of the

water as flowing in one direction. Actually, as water

moves downstream it is also moving back and forth across

the channel. This back and forth movement causes materials

(like silt and sand) to be deposited or dropped at the

inside of a curve, which creates a point bar. Floating

debris builds up on the outside of the curve. For example,

if a log or boulder were put on the inside bank of a curve,

the structure would become buried. In your stream there

may be need to help nature by strategically placing something

that will improve fish habitat. This is covered in later

sections of the manual and a habitat professional will

help you decide on these locations.

- The physical structure of a stream and the quality of

the water flowing in it creates a habitat or home to many

forms of life. The illustration on the next page shows

how a naturally shaped stream gives more useful living

space. Making a stream straighter can dramatically alter

the amount of useful space for fish and other wildlife.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()